Mark III Photonics | Shutterstock

When you think of movie music, what immediately springs to mind? As far as I’m concerned, those two little words conjure up a world of orchestras, of big emotional numbers, of songs you make people listen to when you’re drunk (just me? But the theme from Terry Gilliam’s Brazil is so good!). Movie music is the realm of great composers, people like John Williams and Hans Zimmer and Klaus Badelt, who put together music specifically for one film, one scene and one moment. This is music that is written for a specific purpose, and, while you might well enjoy a spin of, The Magnificent Seven theme, it can’t help but conjure up images of Yul Bryner riding through the desert. Both the sound and the image are inextricably linked. But I’m here to make a fuss about the ways in which film soundtracks has changed, and what exactly that means for the artists taking advantage of this seismic shift.

If you’ve seen any of the big blockbusters released over the last few years — Hunger Games, Twilight, whatever turgid, warmed-over crapola Marvel is injecting into it’s unsuspecting junkies this summer — you’ll have noticed a more names shoehorned into the credits, names that you might well recognize. Bands are getting in on movie soundtracks. And not just one token band writing one big song to promote their new album (well, the promotion certainly comes into it, but more on that later). Entire movie soundtrack albums are made up of bands and artists who spend most of their careers not writing music for end credits. So, where did this begin?

When I peel back my mind-vault and look back over the history of big, modern artists jumping on movie soundtracks (and, more importantly, doing quite well out of it), the first thing that springs to mind is Moulin Rouge. Baz Lurhman’s luridly technicolor continental opera (and I mean all of that in the best possible sense) had a big fat bonus in the form of Lady Marmalade. First released in 1974 by the girl group Labelle, it became the first single of the film’s soundtrack. Featuring big artists like Pink, Lil’ Kim and Christina Aguilera (remember Mya? Yeah, she was there too), it became the third single to hit number one without a commercially available single for the public to get their gritty, sweaty paws on (well, did you see that video? Me-ow). Even now, you’re humming the tune in your head. In a film packed full of popular songs all crammed together into one, there was no better advert for Moulin Rouge than this lusty, spunky take on an oft-forgotten classic. Here, the trade-off is easy to see. Baz got to attract viewers with a song that was played almost perpetually over the course of 2001, and the four artists got to record a few token vocals for a really fun song and rake in the cash and notoriety. This was a win for both parties.

The next big landmark in the transition movie music made into popular culture would be 8 Mile. Eminem, being one of the most iconic rappers of his generation, not only put in an amazing performance as some vaguely bastardized version of himself, but sold us “Lose Yourself” (in amongst some sickeningly excellent rap battles, a phrase I cannot say outloud because I am far too middle-class and uptight). The music was still attached to the moment, to the movie, but the artist was inextricably linked in with his character in the first place, so it worked. 8 Mile was really only one step further than the persona he wore onstage, however veiled, so the music from the film worked both in context and as a single. Once again, the trade-off is clear — rapper facing the possibility of a fading career rocks it up with a movie that allows him to remind everyone of what a great rapper he is. Cunning.

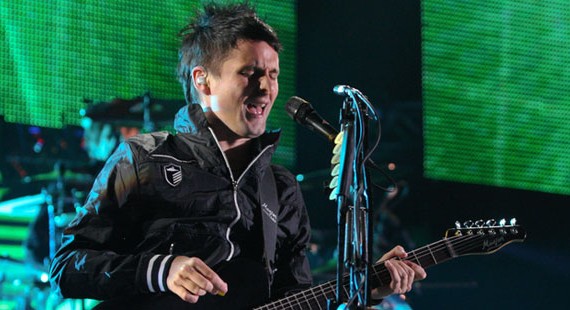

I’m going to skip ahead here a little to one of the most baffling decisions in this article. Do you remember the moment that you first found out Muse would be providing a song for the third film in a very specific trilogy about glittery teenage vampires? While Stephanie Meyer, author of the books upon which the films are based, had been pretty outspoken about her love for the band (one of the reasons they’ve never quite-quite- cracked my top ten) and “Supermassive Black Hole” appeared in the first film, no-one expected Muse to cave and write a song for the grimmest love story of all time. I, for one, think “Neutron Star Collision” happens to be one of their best singles because I am a career contrarian, but either way, it was a turning point. Here was a very alternative band jumping on the bandwagon of one of the most popular and most loathed sensations of this century. And then they just…got on with their careers. And while a thousand internet commenters will whine about Twilight fans turning up on Muse videos, the numbers don’t lie. Attaching one of their songs to a movie that big didn’t do them any harm. At this point, a hundred indie bands cocked their heads to the side and went “huh”.

And then, of course you only have to consider the last few summers to see how modern, name-brand music (if you’ll excuse the term) has become a staple of all the big blockbusters. I managed to drag my boyfriend to The Hunger Games: Catching Fire because he’s a purist and had to hear the new The National song in it’s original setting, for Christ’s sake. I’m sure he’s not the only one who did that (actually, now that I think about it, I really hope he was). But movie soundtracks are now crammed full of bands making the most of the increased exposure a captive audience might give them. While we’re on the subject of Catching Fire, consider the other indie staples who’ve made the cut — The Weeknd, Patti Smith, The Lumineers. While some people have been throwing strops over the choices their favorite bands have made, you can’t really blame them. Write one song, have it featured in a huge movie that you can almost guarantee will be seen (and therefore heard) by millions, then scoop up the cash and any sundry new fans you might have picked up along the way and go back to your day job. Who would say no to that? Hell, use it as a lead single for your next album if you must — just make sure you keep it nice and vague so it sort of fits in with the film as well. “Moody” is the key word here. Also consider the fact that many of the people turning up to see these films, based on young-adult books, might well be going through their indie stage too (I refer to my indie stage as “existence”). The power of connection is not to be underestimated.

Where once studios could get away with sticking a lead single or two onto the album that actually cropped up in the movie, people won’t just buy the CD anymore. With digital downloads, you can choose the ones you really want to hear. From the studio’s perspective, that means commissioning a few artists with a dedicated fanbase to knock out one song, then relying on that fanbase to download it enough times to make it worthwhile — or, better yet, see the dang movie. While you might be up in arms about these bands selling out, would you rather that, or interminable albums with music “Inspired by” the movie, for which the phrase “pissed out” was invented?

There’s also been a trend in a few recent movies to use golden oldies in the soundtrack (see: the soundtrack from Days of Future Past and Guardians of the Galaxy, also the best thing about the latter). Not just sprinkling in a few classics for scene-setting effect, but specifically making a point of featuring them in the movie as vital. You’ll notice that both the movies above are comic-book blockbusters. There’s surely an element of throwing something in for the adults who might have been dragged along with their kids, right? I myself will admit to almost punching a hole in my best friend’s arm when the Banana Splits song came on during Kick-Ass. Music has that power to delight you when it turns up in places you don’t expect, and the big brains behind the movies are working that out and beginning to capitalize on it.

For the first time in a long time, composers are starting to become celebrities. Hans Zimmer carved a legitimate name for himself with the music for Inception. While he might be taking a backseat to a bunch of indie upstarts stealing his job, composed movie music is turning into something you listen to for pleasure again.

But even Has Zimmer ain’t got nothin’ on The Hunger Games soundtrack. Sorry, buddy.

How Movie Soundtracks Changed the Face of the Music industry

When you think of movie music, what immediately springs to mind? As far as I’m concerned, those two little words conjure up a world of orchestras, of big emotional numbers, of songs you make people listen to when you’re drunk (just me? But the theme from Terry Gilliam’s Brazil is so good!). Movie music is the realm of great composers, people like John Williams and Hans Zimmer and Klaus Badelt, who put together music specifically for one film, one scene and one moment. This is music that is written for a specific purpose, and, while you might well enjoy a spin of, The Magnificent Seven theme, it can’t help but conjure up images of Yul Bryner riding through the desert. Both the sound and the image are inextricably linked. But I’m here to make a fuss about the ways in which film soundtracks has changed, and what exactly that means for the artists taking advantage of this seismic shift.

If you’ve seen any of the big blockbusters released over the last few years — Hunger Games, Twilight, whatever turgid, warmed-over crapola Marvel is injecting into it’s unsuspecting junkies this summer — you’ll have noticed a more names shoehorned into the credits, names that you might well recognize. Bands are getting in on movie soundtracks. And not just one token band writing one big song to promote their new album (well, the promotion certainly comes into it, but more on that later). Entire movie soundtrack albums are made up of bands and artists who spend most of their careers not writing music for end credits. So, where did this begin?

When I peel back my mind-vault and look back over the history of big, modern artists jumping on movie soundtracks (and, more importantly, doing quite well out of it), the first thing that springs to mind is Moulin Rouge. Baz Lurhman’s luridly technicolor continental opera (and I mean all of that in the best possible sense) had a big fat bonus in the form of Lady Marmalade. First released in 1974 by the girl group Labelle, it became the first single of the film’s soundtrack. Featuring big artists like Pink, Lil’ Kim and Christina Aguilera (remember Mya? Yeah, she was there too), it became the third single to hit number one without a commercially available single for the public to get their gritty, sweaty paws on (well, did you see that video? Me-ow). Even now, you’re humming the tune in your head. In a film packed full of popular songs all crammed together into one, there was no better advert for Moulin Rouge than this lusty, spunky take on an oft-forgotten classic. Here, the trade-off is easy to see. Baz got to attract viewers with a song that was played almost perpetually over the course of 2001, and the four artists got to record a few token vocals for a really fun song and rake in the cash and notoriety. This was a win for both parties.

The next big landmark in the transition movie music made into popular culture would be 8 Mile. Eminem, being one of the most iconic rappers of his generation, not only put in an amazing performance as some vaguely bastardized version of himself, but sold us “Lose Yourself” (in amongst some sickeningly excellent rap battles, a phrase I cannot say outloud because I am far too middle-class and uptight). The music was still attached to the moment, to the movie, but the artist was inextricably linked in with his character in the first place, so it worked. 8 Mile was really only one step further than the persona he wore onstage, however veiled, so the music from the film worked both in context and as a single. Once again, the trade-off is clear — rapper facing the possibility of a fading career rocks it up with a movie that allows him to remind everyone of what a great rapper he is. Cunning.

I’m going to skip ahead here a little to one of the most baffling decisions in this article. Do you remember the moment that you first found out Muse would be providing a song for the third film in a very specific trilogy about glittery teenage vampires? While Stephanie Meyer, author of the books upon which the films are based, had been pretty outspoken about her love for the band (one of the reasons they’ve never quite-quite- cracked my top ten) and “Supermassive Black Hole” appeared in the first film, no-one expected Muse to cave and write a song for the grimmest love story of all time. I, for one, think “Neutron Star Collision” happens to be one of their best singles because I am a career contrarian, but either way, it was a turning point. Here was a very alternative band jumping on the bandwagon of one of the most popular and most loathed sensations of this century. And then they just…got on with their careers. And while a thousand internet commenters will whine about Twilight fans turning up on Muse videos, the numbers don’t lie. Attaching one of their songs to a movie that big didn’t do them any harm. At this point, a hundred indie bands cocked their heads to the side and went “huh”.

And then, of course you only have to consider the last few summers to see how modern, name-brand music (if you’ll excuse the term) has become a staple of all the big blockbusters. I managed to drag my boyfriend to The Hunger Games: Catching Fire because he’s a purist and had to hear the new The National song in it’s original setting, for Christ’s sake. I’m sure he’s not the only one who did that (actually, now that I think about it, I really hope he was). But movie soundtracks are now crammed full of bands making the most of the increased exposure a captive audience might give them. While we’re on the subject of Catching Fire, consider the other indie staples who’ve made the cut — The Weeknd, Patti Smith, The Lumineers. While some people have been throwing strops over the choices their favorite bands have made, you can’t really blame them. Write one song, have it featured in a huge movie that you can almost guarantee will be seen (and therefore heard) by millions, then scoop up the cash and any sundry new fans you might have picked up along the way and go back to your day job. Who would say no to that? Hell, use it as a lead single for your next album if you must — just make sure you keep it nice and vague so it sort of fits in with the film as well. “Moody” is the key word here. Also consider the fact that many of the people turning up to see these films, based on young-adult books, might well be going through their indie stage too (I refer to my indie stage as “existence”). The power of connection is not to be underestimated.

Where once studios could get away with sticking a lead single or two onto the album that actually cropped up in the movie, people won’t just buy the CD anymore. With digital downloads, you can choose the ones you really want to hear. From the studio’s perspective, that means commissioning a few artists with a dedicated fanbase to knock out one song, then relying on that fanbase to download it enough times to make it worthwhile — or, better yet, see the dang movie. While you might be up in arms about these bands selling out, would you rather that, or interminable albums with music “Inspired by” the movie, for which the phrase “pissed out” was invented?

There’s also been a trend in a few recent movies to use golden oldies in the soundtrack (see: the soundtrack from Days of Future Past and Guardians of the Galaxy, also the best thing about the latter). Not just sprinkling in a few classics for scene-setting effect, but specifically making a point of featuring them in the movie as vital. You’ll notice that both the movies above are comic-book blockbusters. There’s surely an element of throwing something in for the adults who might have been dragged along with their kids, right? I myself will admit to almost punching a hole in my best friend’s arm when the Banana Splits song came on during Kick-Ass. Music has that power to delight you when it turns up in places you don’t expect, and the big brains behind the movies are working that out and beginning to capitalize on it.

For the first time in a long time, composers are starting to become celebrities. Hans Zimmer carved a legitimate name for himself with the music for Inception. While he might be taking a backseat to a bunch of indie upstarts stealing his job, composed movie music is turning into something you listen to for pleasure again.

But even Has Zimmer ain’t got nothin’ on The Hunger Games soundtrack. Sorry, buddy.

Around the Web